Collection overview

The Thomas Edge-Partington 1909-1914 British Solomon Islands Protectorate Cylinder Collection (C83) is a set of eleven wax cylinders recorded in the Solomon Islands, with British Library shelfmarks C83/1510–1520.

The cylinders came from the Royal Anthropological Institute (RAI) in 1983, and the collection was previously called the R.A.I. Bougainville Cylinders within Royal Anthropological Institute Cylinders (C83). Although we have not yet been able to find a document explicitly naming the recordist, all other available evidence very strongly suggests that they were recorded by Thomas Edge-Partington, probably between September 1909 and February 1912.

Research by Vicky Barnecutt, British Library. With thanks to Tim Thomas, University of Otago, and David Akin, University of Michigan, for their help.

The Collection

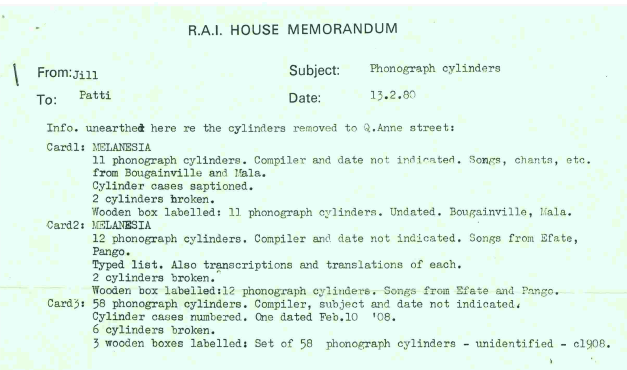

These dark brown wax cylinders came to the British Institute of Recorded Sound (BIRS)1BIRS was founded in 1955, and became part of the British Library in 1983; it is known today as the British Library Sound Archive. in 1983, along with two other cylinder collections.2The collection noted first on the list is currently known as RAI Bougainville Cylinders (C83) and the collection noted last is the RAI Seligman Vedda Cylinders (C83). The collections were accompanied by a memo card, dated 13 February 1980, from the RAI which listed “Info. unearthed here re the cylinders moved to Q. Anne Street”. The memo noted that this collection included “Songs, chants, etc. from Bougainville and Mala”, and that the “compiler and date” were not indicated.

The information that we have comes from writing on the lids and sides of the cylinder boxes. At some point, it was suggested to the British Library that the recordist was either Gerald Wheeler or Richard Thurnwald (Prentice 2001); they were both catalogued as the recordist in the British Library. Wheeler was thought to be the most likely recordist, as some of the recordings have spoken announcements in an English accent, and a number were made on the island of Mono, where Wheeler did anthropological fieldwork. However, research by the True Echoes team at the British Library, helped by Tim Thomas (University of Otago), has led to the conclusion that the cylinders were recorded by Thomas Edge-Partington.

The distinctive handwriting on the labels of the cylinder boxes matches examples of Edge-Partington’s handwriting in the archives of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate, and in the annotations of photographs he collected, copies of which are now in the British Museum. The seven performers that are identified by name on the cylinder lids were all listed by Edge-Partington as being employed by him between 1909 and 1911; they probably worked as part of his police force.

The Recordist

Thomas William Edge-Partington (1883–1920) was the eldest son of James and Ada Edge-Partington. James (1854–1930) was a renowned collector of Pacific artefacts, who was active in both the British Museum and the Royal Anthropological Institute. After a short career in the British Royal Navy, Thomas joined the British Colonial Service and was sent to the British Solomon Islands Protectorate (BSIP) (Neich 2009:91). He served as Resident Magistrate at the government station of Gizo, on the island of Ghizo in the Western Solomons, from December 1904 to May 1909, and then at the government station of Auki on Malaita, from 1 September 1909 to January 1915 (Bennett 1987:401; Akin 2013:39). He spent periods away from the Solomon Islands on furlough. Thomas’ family donated the photograph albums from his time in the Pacific to the British Museum, and we have used these photographs to illustrate this collection.

This photograph shows Thomas Edge-Partington. Although it is undated, contextual information indicates that it was taken at Government House, Auki, Malaita, between February 1913 and January 1915.

Gizo

Edge-Partington arrived at Gizo as Resident Magistrate in December 1904 and stayed there until 31 May 1909, with two periods of furlough (August 1905 ‒ January 1906, 12 May ‒ 20 July 1908) (Bennett 1987:398). Whilst stationed at Gizo, Edge-Partington evidently travelled at least once to Roviana Lagoon, as he described the funeral of Ingava, “Chief of Rubiana”, in 1906 (Edge-Partington 1907:22–23). In the same short article, he also noted that there had been “a tremendous lot of sickness among the natives, both in Simbo and Rubiana … It is carrying off all the old men and women.”

During this period, Edge-Partington had a relationship with a woman from Simbo Island (Moore 2019:294); it is not clear whether she lived on Ghizo or Simbo. He was transferred away from Gizo in July 1909, when colonial officials became aware of this relationship. He had to apologise to both the Resident Commissioner, Charles Morris Woodford, and the High Commissioner for his behaviour, and received an official reprimand from London (Moore 2019:294).3The High Commissioner of the Western Pacific High Commission was at this time Sir Everard im Thurn, Governor of Fiji. Presumably due to his young age and otherwise good behaviour, Edge-Partington was not dismissed, but instead was placed on probation and moved to Malaita to establish the first government station there. Woodford (1852–1927) was stationed in Tulagi, the capital, during this period.

Malaita

When he arrived on 1 September 1909, Edge-Partington, as District Magistrate, was Malaita’s first resident government officer. The government station was established at Rarasu on the central-west coast of Malaita, and was named Auki after the nearby island of ‘Aoke, Auki, or Kwaibala (Akin 2013:37). Edge-Partington wrote his address as Quaibala, Mala. Rarasu / Auki was at the northern end of the Langalanga Lagoon. Also known as Akwalaafu, the lagoon is 21 km long and just under 1 km wide. The people of the lagoon have referred to themselves as, and been called, “saltwater people” since the nineteenth century, to distinguish them from the “bush” people of the mainland.4https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Langa_Langa_Lagoon. In local languages, “Ta`a i asi.” They live on small islands that have been artificially built up over the years with coral blocks on the sand bars of the lagoon.

This photograph of houses on one of the islands of the Langalanga Lagoon was taken in 1907 by the Australian photographer George Rose. Thomas included many of Rose’s photographs in his albums.

Edge-Partington brought with him about 28 policemen and some convicts from the Western Solomon Islands. These men worked to help establish the station as he could not find Malaitans willing to work for him (Akin 2013:35, 38). Letters between Edge-Partington and Woodford in the archives of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate indicate that Edge-Partington had a difficult task trying to extend government control into the Malaitan mainland. He evidently found his job frustrating, in particular the lack of adequate support from his superiors and the presence of just a small police force (Akin 2013:39).

This photograph of the government station at Auki, Malaita, is not dated, but must have been taken sometime between 1909 and January 1915; with a probable date of around 1912-1914.

On 28 February 1910, Edge-Partington listed 28 men as the “labour on the Government Station, Mala.” Most of these men had signed on in September 1909 for a period of one year, at a wage of £1 a month. Included in this list was a man named Kurura from the Shortland Islands on 1 September (Edge-Partington 1910a). On 9 June 1910, Edge-Partington wrote to Woodford discussing the possibility of recruiting men from Rubiana [Roviana Lagoon], Saikile, Lukuru [on Rendova], Simbo, Treasury [Mono], Shortlands [Alu], Vella Lavella, and Choiseul [Lauru] (Edge-Partington 1910c). It is not clear whether he managed to visit all of these places.

On 1 November 1910, responding to a request from Woodford to list “all police, prisoners, arms and accoutrements on [Mala] Station,” he enclosed “a complete list of everything and everybody” (Edge-Partington 1910d). This list included six prisoners and 37 workers; it is not clear whether these were all policemen. They were each paid £1 a month, apart from one man called Sibiau from Alu who received £2 a month. He had been recruited in September 1909. The list included:

- Kurura (Sept 19th, Alu)

- Pilot (Sept 19th, Alu)

- Kaga (Sept 24th, Alu)

- Kamanda (Sept 1st 1910, Banietta)

- Osopo (Sept 1st 1910, Banietta)

- Angabili (Sept 1st 1910, Banietta)

- Peloko (Sept 1st 1910, Vangunu

(Edge-Partington 1910d)

Edge-Partington previously noted that he employed Kurura in September 1909. It seems likely from the information listed that Pilot and Kaga started work at the same time, but they were not listed on the document from 28 February 1910. The others started in September 1910. All these men were noted as performers on the cylinder recordings, and their places of origin roughly correspond with the languages of the recordings. This is discussed further in the Performers section. On 30 March 1911, Edge-Partington wrote to Woodford noting that he was sending three of the police “whose times are up and who wish to be paid off” to Woodford at Tulagi. These three men were Pilot, Kaga, and Sakuri.

It is possible that these men appear in this photograph of the British Solomon Islands Police Corps from Edge-Partington’s photograph album, but no names, place or date is recorded.

Edge-Partington noted that he visited all the islands in Langalanga Lagoon on 21 March 1910 and met with the “principal” men of each island (Edge-Partington 1910c). He also noted in the District Officer’s Diary for 1910 that he visited Alite Island, Langalanga Island, Kwalafou Island, and Laulasi Island (Edge-Partington 1910f).

He remained at Auki until January 1915, with one year of furlough between 22 February 1912 and 26 February 1913 (Bennett 1987:401). During this furlough, he got married and his new English wife, Mary (1883–1971), accompanied him on his return to Malaita. He resigned his position on 5 Dec 1914 (Akin 2013:39) and left the region on 26 January 1915.

This photograph, again undated, shows Thomas and Mary Edge-Partington, presumably in Malaita, between February 1913 and January 1915.

Death

In 1915, Thomas and Mary moved to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) where he worked for a plantation company. He died there of influenza on 20 April 1920 (Neich 2009:92); his widow, Mary, was pregnant with their son, Thomas Keppel, at the time.

History of the Cylinders

This collection of cylinders came into the British Institute for Recorded Sound from the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1983, with two other cylinder collections, RAI Vanuatu and RAI Seligman Vedda Cylinders (C83). There was no accompanying documentation for this collection, apart from a memorandum noting all three cylinder collections. It was originally documented as RAI Bougainville (C83).

Thomas Edge-Partington’s cylinder collection may have been given or sold directly to the RAI by his father James, or it may have been transferred first to the British Museum, and from there went to the RAI. Further research on this matter is being conducted.

Two of the cylinders have a date written on the lid in ballpoint pen, ‘6-7-83’ i.e. 6 July 1983. This indicates that the collection was dubbed on or around that date at the British Library. The cylinders were copied onto DAT at some point before 1993, when Alan Ward (British Institute of Recorded Sound) offered Jonathan Benthall, Director of the Royal Anthropological Institute, DAT copies of all of the C83 recordings.5Letter from Alan Ward to Jonathan Benthall, 3 November 1993. Don Niles at the Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies received a CD of the recordings and photocopies of the cylinder lids in 2006.6Email from Don Niles to Janet Topp Fargion, 9 June 2006.

At some point, it was suggested to the British Library that the recordist was either Gerald Wheeler or Richard Thurnwald (Prentice 2001); they were both catalogued as the recordist in the British Library. Wheeler was thought to be the most likely recordist, as some of the recordings have spoken announcements in an English accent, and a number were made on the island of Mono, where Wheeler did anthropological fieldwork. Tim Thomas suggested that the recordist might have been Thomas Edge-Partingon; Edge-Partington’s distinctive handwriting provided evidence for this connection.7Email from Tim Thomas to Vicky Barnecutt, 10 December 2020.

The True Echoes team contacted Dr Caroline Adams, an archivist, a historian, and an expert in deciphering old handwriting. She compared the labels on the cylinder lids with copies of Edge-Partington’s handwriting from the archives. She replied that in her opinion, the cylinders are labelled by Edge-Partington. Her reasons are graphology-based:

His ‘u’ and ‘n’ look the same; His ‘l’ is looped the same way at the top; He has a distinctive ‘v’ which rolls over, as in ‘bougainville’ on the cylinder and ‘every’ in the correspondence; His upper case ‘G’s are formed in the same way; So are his ‘t’s; The ‘g’ has a straight tail with no loop; The ‘I’s are consistently dotted over the minim; The upright stroke of the ‘p’ goes slightly higher than the loop.8Email from Caroline Adams to Vicky Barnecutt, 28 April 2021.

As a result of the historical research undertaken by the True Echoes team, the British Library decided to rename the collection the Thomas Edge-Partington 1909-1914 British Solomon Islands Protectorate Cylinder Collection (C83) to reflect the recordist and recording location, using the country name contemporary to the recordings.

Related sound collections

The British Library’s RAI Vanuatu cylinder collection and RAI Seligman Vedda Cylinders (both C83) also came from the Royal Anthropological Institute, although there is no indication that the recordings or recordists are connected. The British Library has two other cylinder collections which include cylinders that were probably recorded around the same time as, and in some similar locations to, this collection: the WHR Rivers and Arthur M Hocart 1908, New Georgia group, British Solomon Islands Protectorate Cylinder Collection (C108) and the Unidentified Cylinders collection (C680). These cylinders were recorded by W. H. R. Rivers and A. M. Hocart. Hocart also sent nineteen cylinders to Carl Stumpf at the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv that he recorded in Roviana Lagoon between 2 and 15 October 1908 (Ziegler 2006:155).

Related artefact collections

Thomas Edge-Partington made an extensive artefact collection for his father, James, during his time in the Solomon Islands. James wrote to Augustus Hamilton at the Auckland Museum in May 1912 noting that “My son has just landed from the Solomons on long leave and has brought home some good things for my museum” (quoted in Neich 2009:92). James collected around 423 objects from the Solomon Islands in total, retaining 326 of them (Neich 2009:86). In the final manuscript of his collection, James noted that around 120 artefacts were collected by Thomas during his time in the Solomon Islands. He supplied artefacts to the British Museum, Pitt Rivers Museum and the Horniman Museum (Rubenstein 2013:338), and after the First World War, his remaining collection was acquired by Auckland Museum. However, we could not identify any musical instruments or ritual paraphernalia related to the sound recordings among the artefacts collected by James or Thomas.

The British Museum holds around 40 objects from the Solomon Islands that were either purchased from or donated by James, including objects received from his son (Rubenstein 2013:338). It is possible that the cylinders recorded by Thomas were donated or sold by James to the British Museum at the same time as these artefacts. The Pitt Rivers Museum has around 9 objects from James; it is not clear which artefacts came from Thomas. The Horniman Museum also has objects collected by James.

Of the 90 artefacts collected by James Edge-Partington in the Auckland Museum, “about 37 are from Malaita, 4 from Choiseul, 20 from Rubiana, 4 from Simbo, 2 from Vella Lavella, 11 from Bougainville, and about 12 unlocalised beyond ‘Solomon Islands’” (Neich 2009:92).

Thomas’ widow Mary donated an important collection made with her husband to the British Museum in 1921. This consisted of “some 40 Solomon Islands artefacts – including body ornaments, figures and dance-shields” (Rubenstein 2013:338). The body ornaments comprise 14 armbands from the Shortlands-Bougainville region and a number of beaded belts and ear ornaments from Malaita. The dance-shields were also from Malaita, but no further provenance information was recorded, so we do not know if these came from the Langalanga Lagoon.

The British Museum holds digital copies of most of Thomas Edge-Partington’s photographic collection. Thomas collected approximately 600 photographs of the islands from various sources, including both photographs he took himself and prints from John Watt Beattie, George Rose, and others. Beattie was State Photographer of Tasmania, and he visited the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu on the Melanesian Mission ship Southern Cross in 1906. He took hundreds of photos and kept a diary of his tour. Rose was also an Australian photographer who travelled through the Solomon Islands in 1907 as part of a world tour. Edge-Partington acquired a number of prints and stereograph cards from Rose (Burt 2016:214), and a number of plates from Beattie, presumably when they passed through Gizo on their voyages.

- Akin, David W. 2013. Colonialism, Maasina Rule, and the Origins of Malaitan Kastom. Pacific Islands Monograph Series 26. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

- Bennett, J. A. 1987. Wealth of the Solomons. Pacific Island Monograph Series, 3. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Burt, Ben. 2015. Malaita: A Pictorial History from Solomon Islands. London: British Museum.

- Eberhard, David M., Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2021. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twenty-fourth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- Edge-Partington, James. 1890. An Album of the Weapons, Tools, Ornaments, Articles of Dress Etc. of the Natives of the Pacific Islands. Vol. 1. Manchester: E. P. and Charles Heape.

- Edge-Partington, James. 1895. An Album of the Weapons, Tools, Ornaments, Articles of Dress Etc. of the Natives of the Pacific Islands. Vol. 2. Manchester: E.P. and Charles Heape.

- Edge-Partington, James. 1898. An Album of the Weapons, Tools, Ornaments, Articles of Dress Etc. of the Natives of the Pacific Islands. Vol. 3. Manchester: E.P. and Charles Heape.

- Edge-Partington, Thomas William. 1906. “Note on the Food Bowl from Rubiana, New Georgia.” Man 6: 121.

- Edge-Partington, Thomas William. 1907. “Ingava, chief of Rubiana, Solomon Islands: Died 1906.” Man 7/15: 22–23.

- Edge-Partington, Thomas William. 1910a. Letter to Woodford 28 February 1910. BSIP 14/40. Honiara: Solomon Islands National Archives.

- Edge-Partington, Thomas William. 1910b. Letter to Woodford 21 March 1910. BSIP 14/40. Honiara: Solomon Islands National Archives.

- Edge-Partington, Thomas William. 1910c. Letter to Woodford 3 May 1910. BSIP 14/40. Honiara: Solomon Islands National Archives.

- Edge-Partington, Thomas William. 1910d. Letter to Woodford 9 June 1910 on finding Mala labourers. BSIP 14/40. Honiara: Solomon Islands National Archives.

- Edge-Partington, Thomas William. 1910e. Letter to Woodford 1 November 1910 station list. BSIP 14/40. Honiara: Solomon Islands National Archives.

- Edge-Partington, Thomas William. 1910f. Notes from District Officer’s Diary 1910. BSIP 15/8. Honiara: Solomon Islands National Archives.

- Hocart, Arthur Maurice. 1922. “The Cult of the Dead in Eddystone of the Solomons.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 52: 259–305.

- Hocart, Arthur Maurice. 1931. “Warfare in Eddystone of the Solomon Islands.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 61: 301–324.

- Keesing, Roger M., and Peter Corris. 1980. Lightning Meets the West Wind: The Malaita Massacre. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Lawrence, David 2014. “The Plantation Economy.” In The Naturalist and His “Beautiful Islands”: Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific, 243–286. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Laycock, Donald. 2003. A Dictionary of Buin. Pacific Linguistics. Canberra: ANU.

- Moore, Clive. 2017. Making Mala: Malaita in Solomon Islands, 1870s–1930s. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Moore, Clive. 2019 Tulagi: Pacific Outpost of British Empire. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Neich, Roger. 2009. “James Edge-Partington (1854–1930): An Ethnologist of Independent Means.” Records of the Auckland Museum (Auckland War Memorial Museum) 46: 57– 110. (pp. 89–92 ‘Thomas Edge-Partington in the Solomon Islands’)

- O’Brien, Aoife. 2010. “The Professional Amateur: An Exploration of the Collecting Practices of Charles Morris Woodford.” Journal of Museum Ethnography 23: 21–40.

- O’Brien, Aoife. 2011. “Collecting the Solomon Islands: Colonial Encounters and Indigenous Experiences in the Solomon Island Collections of Charles Morris Woodford and Arthur Mahaffy (1886–1915).” PhD thesis, University of East Anglia.

- Prentice, Will. 2001. Report on the “Wheeler/Thurnwald” Cylinder Collection C83. London: British Library Sound Archive.

- Rivers, William Halse Rivers. 1914. The History of Melanesian Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Rubenstein, Geoff. 2013. “Significant Collectors and Donors of the British Museum Melanesia Collection.” In Melanesia: Art and Encounter, edited by Lissant Bolton, Nicholas Thomas, Elizabeth Bonshek, Julie Adams, and Ben Burt, 335–343. London: British Museum Press.

- Wheeler, Gerald Camden. 1913. ‘A Text in Mono Speech (Bougainville Strait, Western Solomon Islands)’, Anthropos 8:4 738-753

- Wheeler, Gerald Camden. 1926. Mono Alu Folklore. (Bougainville Straits, W. Solomon Islands.) London: G. Routledge & Sons.

- Ziegler, Susanne. 2006. Die Wachszylinder des Berliner Phonogramm-Archivs. Veröffentlichungen des Ethnographischen Museums Berlin, 73. Berlin: Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.